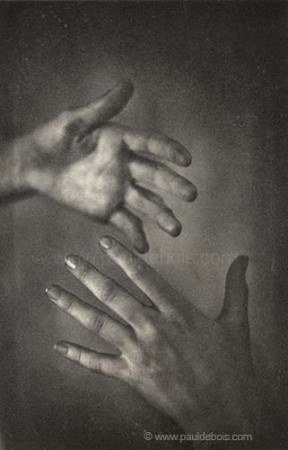

One of my last Kodachrome images - taken in 1990

I’ve recently been reading postings on forums regarding the demise of Kodachrome, a film which has been used by generations of photographers, amateurs and pros alike. Introduced in 1935, it was available in various forms until 2009, when Kodak announced it would cease production due to a fall in demand. If you are one of the few who have any rolls left, remember you have until 30th December 2010 to get it to Dwayne’s Photos in Parsons, Kansas, the last place still processing this film, when even they will stop.

I shot my first rolls of Kodachrome in 1979 and was amazed at the saturated colour which could be achieved compared to contemporary offerings, such as Ektachrome 64, also from the Kodak stable. At that time, most of my professional work was in black and white and I don’t remember using it for commercial photography until 1988, when I started to contribute to Car Magazine.

Car was the leading automotive magazine of the period, and under the art direction of Adam Stinson, it produced some of the most innovative car photography in Europe and the USA, influencing many magazines worldwide. Adam favoured Kodachrome, so when I was invited to start shooting for Car, I spent many an hour negotiating the Fulham Palace Road during the London rush hour, trying to get to the Kodachrome collection/delivery point in time to meet the evening deadline. At that time, barmy as it may seem, film shot in the UK could only be processed in Paris. I think it was a 24 hour turnaround, and it was always an event opening each of the returned boxes and spreading the frames, in their classic card mounts, over the lightbox.

Ultimately, for me and I suspect for many others, this impractical method of processing was the beginning of Kodachrome’s downfall. As a new generation of films emerged around 1990 which provided equally great colour rendition and saturation, practical alternatives were established. For many Fuji Velvia, still in production today, became the alternative of choice. It was possible get this, and other E6 slide films, processed quickly and easily and in front of an art director in under two hours. Commercially it made sense to move away from Kodachrome – sadly, it no longer fitted into a lot of photographers’ workflows. Then digital came of age!

The last time I used Kodachrome was around 1990, when I was asked to shoot a series of car books. After the first book, I made several calls to the publisher asking to switch from Kodachrome. He saw the quality of the Velvia test rolls I had sent, and (reluctantly at first) agreed to let me shoot the remaining books on Fuji stock. To this day, I still think this was the right decision!

Despite it being something that I currently wouldn’t have much use for, I’d love to see Kodachrome survive in some form, as it adds to the flavour and mix of the photographic world. Unfortunately the process is so complicated, I doubt it will be viable for anyone to try to take it over.

As a footnote, Polaroid pretty much finished instant film production a couple of years ago – but with the Impossible Project taking over what remained of the production plant, the concept of Polaroid instant film is still with us. (Fuji instant film has been in constant production for many years, but doesn’t have the same following). Polaroid themselves have taken an about-turn and have produced a new camera and instant film, the Polaroid 300 – and have appointed Lady Gaga as their Creative Director, so there may well be hope for analogue devotees!